Scroll down for the english version

(Esclusiva Campadidanza)

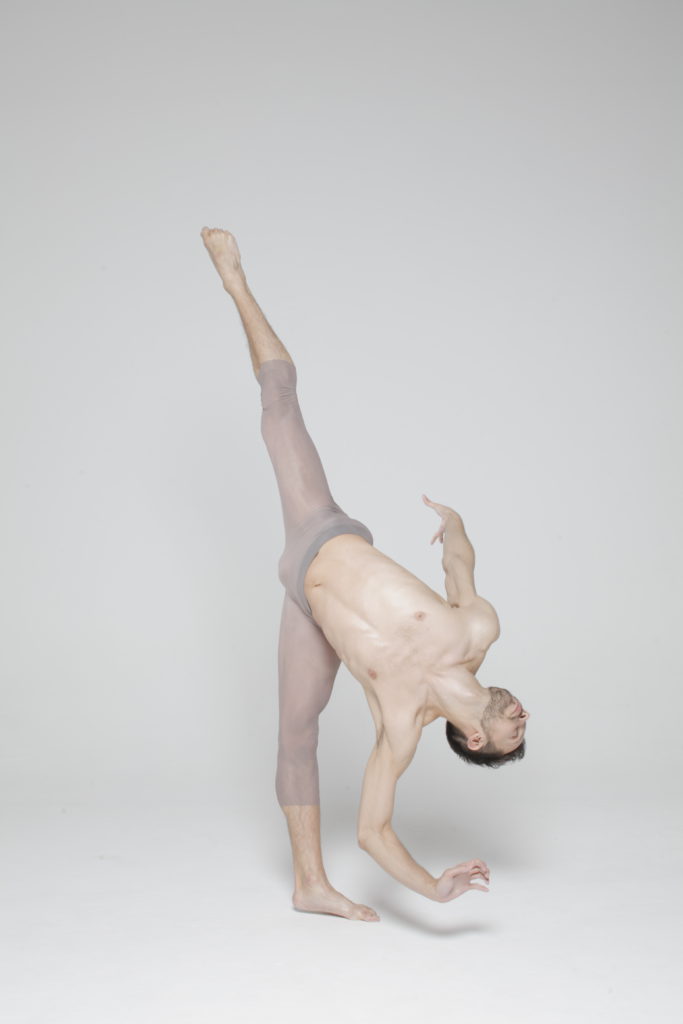

Nato a Colleferro (RM), a soli 36 anni Davide Di Pretoro gira il mondo come re-stager, assistente e coreografo di Wayne Mc Gregor. Quando non viaggia, risiede a Berlino dove danza per la Sasha Waltz & Guests, della quale è anche assistente alla coreografia e direttore di prove.

Ma facciamo un passo indietro…

Davide, quando e come ti sei avvicinato alla danza?

Quando ero piccolo, in televisione era ancora possibile assistere a trasmissioni di danza di altissimo livello. Rimanevo incantato nel vedere i virtuosismi dei ballerini che volavano in aria e giravano come trottole senza nessuno sforzo. Il balletto mi piaceva così tanto da scriverne ‘poesie’ e farne disegni nel mio quaderno. Nonostante la mia passione fosse evidente, non ho iniziato subito a studiare danza. Prima ho praticato la ginnastica artistica. Soltanto a 13 anni, per la prima volta, mi sono iscritto ad una scuola per studiare danza classica.

La tua formazione, quindi, è stata prevalentemente classica?

Dopo il primo anno, nonostante il classico fosse sempre il genere che preferivo, ho iniziato a studiare anche tecnica contemporanea. Sebbene a livello razionale non ne fossi consapevole, quest’apertura mi ha consentito di trovare un’altra logica del corpo, un modo di muovermi più organico. Pur fedele al rigore della danza classica, lentamente il mio movimento si ‘liberava’.

Fino a che età sei rimasto a Colleferro?

Ci sono rimasto fino a 17 anni, poi sono andato all’Accademia Nazionale di Roma e, in quello stesso periodo, ho lavorato nella compagnia Danza Prospettiva di Vittorio Biagi. È stata la mia prima esperienza con una compagnia professionale. Ricordo che per me fu dura: il lavoro era molto tecnico e i miei colleghi molto virtuosi. Avevo anche un solo che ripetevo sempre. Mi impegnai moltissimo perché volevo essere all’altezza dei miei colleghi. Ricordo ancora le parole del maestro Biagi quando, dietro le quinte, mi disse: “Davide, tu sei molto bravo ma devi studiare. Mi raccomando studia…”. Ed è esattamente quello che ho fatto! Ma il mio periodo romano è durato poco, a 20 anni ero già in Francia.

Da Roma a Parigi, come sei arrivato a lavorare con Bruno Agatí?

È stato un caso… Stavo facendo uno stage in Umbria con Bruno Collinet, il quale parlò di me a Bruno Agatí che stava cercando un ballerino per la sua Carmen. Così, in modo inaspettato, mi sono ritrovato a Parigi per imparare le coreografie di questo nuovo spettacolo che, dopo pochi mesi, avrebbe debuttato allo Stade de France.

Come ti sei trovato in Francia? Hai trovato un ambiente simile – nell’organizzazione e nell’approccio al lavoro – a quello che avevi conosciuto e frequentato in Italia?

Devo dire che in principio mi sono sentito molto spaesato. Non solo il francese che avevo imparato a scuola non mi consentiva di comprendere i parigini, ma, durante la prima settimana, si verificarono anche un paio di episodi che resero il mio arrivo degno di un thriller. Una mattina, bussò alla porta di casa la polizia accusando me e il mio coinquilino, ballerino anche lui, di essere degli squatter. Nonostante l’appartamento ci fosse stato assegnato dalla compagnia, la proprietaria aveva fatto una denuncia, così ci portarono in caserma senza che noi ne capissimo il motivo. Ci tennero lì un giorno intero, finché non venne un responsabile della compagnia a dare spiegazioni per farci liberare. Dopo pochi giorni, mi rubarono anche il portafogli all’uscita dello stadio dove avevamo le prove. Insomma, non fu esattamente il benvenuto che speravo. A parte queste disavventure, mi sono trovato molto bene. Sono entrato nel giro dei ballerini free lancer di Parigi, che avevano altri riferimenti, altri standard. Anche nel lavoro c’era un’altra organizzazione.

Cosa intendi per altri riferimenti?

Intendo dire che il tipo di danza contemporanea che si faceva in Francia era abbastanza diverso da quello che si vedeva in Italia. Mentre nel nostro Paese lo studio del contemporaneo era ancora legato alle tecniche Cunningham, Graham o Limón, a Parigi era già molto più diffusa la tecnica release o altri stili più liberi e meno codificati. Anche le compagnie a cui i danzatori facevano riferimento erano diverse. Lì, per esempio, ho conosciuto il lavoro della coreografa spagnola Blanca Li o quello di Abou Lagraa. Ricordo che un altro grande nome che circolava molto nell’ambiente era quello di Angelin Preljocaj. Soprattutto nel primo decennio del 2000, erano tantissimi i danzatori che cercavano di entrare nella sua compagnia.

E in che modo l’organizzazione era diversa?

Per quanto riguarda l’organizzazione, in Francia – sin dagli anni ’60/’70 – esiste la categoria degli ‘intermittence du spectacle’ (intermittenti dello spettacolo) a cui, considerata la natura ‘saltuaria’ o non continuativa del lavoro degli artisti, spetta un regime di indennità di disoccupazione particolare. Insomma, il mestiere del ballerino è più tutelato e, anche socialmente, tenuto in diversa considerazione rispetto all’Italia.

A proposito di Ballet Preljocaj, quando e come sei entrato in compagnia?

Era il 2006. In quel periodo lavoravo per due compagnie, per la Georges Momboye a Parigi e la Thor in Belgio. Feci l’audizione per Preljocaj quando la sede era ancora a la Cité du Livre di Aix-en-Provence, poi ci spostammo presso il nuovo centro Pavillon Noir (c’è il mio nome – insieme a quello degli altri ballerini – inciso su uno dei gradini del centro!). Quella con Preljocaj è stata un’esperienza molto bella, ho imparato tanto sulla precisione, sulla velocità e sopratutto sul modo di ‘vivere’ in una compagnia tanto grande, sempre in tournée. Dopo due anni, ho iniziato a sentire il bisogno di fare qualcosa di diverso, di esplorare nuove possibilità di movimento, quindi, ancora una volta ho cambiato, mi sono trasferito in Olanda.

Hai trovato ciò che cercavi nel Dansgroep Amsterdam diretto da Itzik Galili & Krisztina De Chatel?

Solo in parte. Preljocaj è un grande coreografo, ma il suo lavoro è prevalentemente corale e i danzatori sono al servizio della sua creatività. In tal senso, bisogna conformarsi e uniformarsi gli uni agli altri, a discapito delle caratteristiche individuali di ogni singolo danzatore. È per questo che, pur rendendomi conto di quanto fosse stato importante imparare il suo stile e prendere il più possibile dai suoi insegnamenti, a un certo punto ho voluto sperimentare qualcosa di diverso. Con Galili, sicuramente ho trovato più libertà. Il suo era un movimento più fluido, con un approccio e un training differente, ma ancora non era ciò che cercavo.

È corretto dire che la svolta è arrivata con Wayne McGregor?

Assolutamente! I tre anni trascorsi a Londra con la Random Dance sono stati tra i più importanti non solo per la mia formazione professionale, ma anche per la mia sensibilità artistica e umana. Quello che Wayne McGregor mi ha dato, infatti, è tantissimo sotto entrambi i punti di vista. Il suo lavoro è molto stimolante, sollecita la connessione che c’è tra mente e corpo. Spesso, per dare un fondamento teorico alla sua ricerca, si avvale della collaborazione di neuro-scienziati che supportano le sue intuizioni. Con lui, infatti, non si tratta semplicemente di imparare una frase e ripeterla, ma di affrontare una vera e propria sfida con sé stessi per creare questo collegamento. Se apparentemente la sua danza può sembrare fredda e tecnica, osservando attentamente le sue coreografie si capisce, invece, che quella fisicità riesce a portarti a un livello molto più intimo, che trascende il corpo. Quest’aspetto del suo lavoro ne costituisce la caratteristica più interessante, ma questa non è la sola cosa che mi ha lasciato.

Quale altro insegnamento ti ha trasmesso?

La capacità di gestire e organizzare – con professionalità e con la necessaria sensibilità verso il singolo – un gruppo di persone, per realizzare una performance. Durante il periodo che ho trascorso in compagnia, periodicamente dovevo tenere un workshop con studenti, bambini o anziani che non avevano esperienza nella danza. Attraverso questi laboratori, cosiddetti ‘creative learning’, non solo ho imparato a gestire un gruppo e ad adattarmi sempre a persone e situazioni diverse, ma ho altresì imparato a usare la creatività altrui, fino a riuscire, con il materiale di chi partecipava workshop, a creare una vera e propria coreografia.

Wayne McGregor ti ha anche accordato molta fiducia. Mi racconti come e quando ha iniziato a farti montare le sue coreografie per alcune tra le maggiori compagnie di danza?

È stato proprio attraverso l’esperienza acquisita con i creative learning e grazie al mio lavoro in compagnia (in particolare alla mia capacità di sentire il collegamento tra mente e corpo per lui tanto importante), che nel 2013 Wayne McGregor mi ha proposto il lavoro di re-stager. Ho iniziato con lavori piccoli, prima affiancandolo e poi da solo. È una grande responsabilità, ma una soddisfazione ancor più grande quella di girare il mondo facendo questo bellissimo lavoro per compagnie quali: Ballet de l’Opéra National de Paris, Joffrey Ballet Chicago, Hessisches Staats Ballet, Ballet Junior de Genève, TISCH School of the Arts at New York University, Milano Contemporary Ballet, Teatro alla Scala di Milano, The Royal Ballet, Polish National Ballet.

Ma voltiamo pagina… Come è nata la collaborazione con Sasha Waltz?

Dopo un periodo ad Atene nella compagnia Apotosoma Dance Company di Andonis Foniadakis, sono tornato in Italia dove ho lavorato con Virgilio Sieni. In quello stesso periodo sono stato invitato da Sasha Waltz, che avevo conosciuto anni prima in occasione dell’inaugurazione del Maxxi a Roma, a partecipare a uno stage tenuto dalla Company Blu. Una settimana di improvvisazione e sei showing.Alla fine del workshop si è aperto un’altro capitolo della mia vita professionale: ho iniziato prima a danzare per la Sasha Waltz & Guest e poi a lavorare come assistente alla coreografia e direttore prove della compagnia.

Ci sono ancora un paio di cose che mi piacerebbe domandarti…

Alla luce delle tue esperienze in giro per il mondo, qual’è il tuo rapporto e cosa pensi della danza in Italia?

Devo dire che per tanto tempo, quando andavo ad insegnare in Italia, trovavo molti danzatori bravissimi (se ne incontrano tanti, infatti, nelle compagnie di tutto il mondo), ma il livello della danza non era all’altezza di quello di altri Paesi europei. Oltretutto, in Italia ho tutt’ora l’impressione che quello della danza sia un sistema chiuso. Nonostante le esperienze fatte all’estero, ho sempre dovuto lottare per essere retribuito il giusto e ho sempre avuto la sensazione che se sei giovane, a dispetto del tuo curriculum, non sarai mai considerato all’altezza di incarichi importanti. A riprova di ciò, posso dire che solo dopo aver montato un pezzo di Wayne McGregor presso il teatro Alla scala di Milano e che, di conseguenza, il mio nome ha iniziato ad essere associato al famoso teatro d’opera, la mia reputazione è cresciuta. Questo la dice lunga su come funzionano le cose nel nostro Paese. Devo riconoscere, però, che sempre di più, negli ultimi tempi, trovo piccole realtà che cercano di promuovere la ricerca e una danza più ‘internazionale’.

Se potessi esprimere un desiderio per il tuo futuro professionale, cosa ti augureresti?

Sicuramente voglio migliorare e crescere ancora come re-stager e, come danzatore, sento di avere ancora molto da dare e ricercare. Sono queste le cose che cercherò di fare nel mio futuro professionale, ma se dovessi sperare in un altro traguardo, penso che mi piacerebbe lavorare con la Tanztheater Wuppertal di Pina Baush o con Rosas di Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker.

Davide, grazie mille e un grande in bocca a lupo, allora.

Davide Di Pretoro was born in Colleferro (RM), at the age of 36 he started to travel the world as Wayne McGregor’s re-stager, assistant and choreographer. When he isn’t traveling, he lives in Berlin where he dances for Sasha Waltz & Guests, of which he is also an assistant choreographer and rehearsal director. But let’s rewind for a second…

Davide, when and how did you become involved in dance?

When I was a child, it was still possible to watch top-level dance shows on television. I was enchanted by the virtuousity of the dancers flying through the air and twirling like spinning tops without any effort. I liked ballet so much that I wrote “poems” and drew scenes in my notebook. Although my passion was obvious, I didn’t immediately start studying dance. First I practiced artistic gymnastics. Only at the age of 13 did I enrol in a school to study ballet.

So your dance education was mostly classical?

After the first year, although ballet was always the form that I preferred, I also started to study contemporary technique. Even if I wasn’t aware of it on a rational level, this opening into something new allowed me to find a different logic of the body, a more organic way of moving. Whilst remaining faithful to the rigor of classical dance, my movement slowly “freed itself”.

Until when did you live in Colleferro?

I stayed there until I was 17, then I went to the National Academy of Rome and during that same period, I worked for Vittorio Biagi’s Danza Prospettiva company. It was my first experience with a professional company. I remember it was hard for me: the job was very technical and my colleagues were very talented. I also had a solo that I repeated thousands of times. I worked very hard because I wanted to live up to my colleagues’ expectations. I still remember Maestro Biagi’s words when, behind the scenes, he told me: “Davide, you are very good but you must study, make sure that you follow my advice…”. And that’s exactly what I did! But my stint in Rome did not last long. At the age of 20, I was already in France.

From Rome to Paris, how did you come to work with Bruno Agatí?

It was a coincidence… I was attending a workshop in Umbria lead by Bruno Collinet, who spoke about me to Bruno Agatí who, at the time, was looking for a dancer for his Carmen. So, in an unexpected way, I found myself in Paris to learn the choreography for this new show that, after a few months, was going to debut at the Stade de France.

How was your experience in France? Did you find a similar environment – in matter of organization or approach to work – compared to the one you had known in Italy?

I must say that in the beginning I felt very confused. Not only was the French I learned at school insufficient to allow me to understand the Parisians but, during the first week there were also a couple of episodes that made my arrival worthy of a thriller. One morning the police knocked on the door accusing me and my roommate, also a dancer, of being squatters. Although the apartment had been assigned to us by the company, the owner had made a complaint, so they took us to the police station without us knowing why. They kept us there for a whole day, until a company manager came to clear the matter up in order to get us released. After a few days, my wallet was stolen at the exit of the stadium where we were carrying out rehearsals. In short, it was not exactly the welcome I was hoping for. Apart from these mishaps, I was quite happy. I joined the Paris freelancer dancers, who had other references, other standards. Work was also organized in a different way.

What do you mean by other references?

I mean that the type of contemporary dance that took place in France was really interesting and quite different from what was being shown in Italy at that time. Whilst in our country the study of contemporary dance was still stuck with Cunningham’s, Graham’s or Limón’s techniques, in Paris the release technique or other freer and less codified styles were already much more widespread. Even the companies that the dancers referenced or were inspired by were different. There, for example, I got to know the work of the Spanish choreographer Blanca Li and also Abou Lagraa. I remember that another great name that circulated a lot in the dance environment was that of Angelin Preljocaj. Especially in the first decade of 2000, there were many dancers trying to join his company.

And how was the organization different?

In France – since the 60s / 70s – there has been the category of ‘intermittence du spectacle‘ which given the ‘intermittent’ or non-continuous nature of artists’ work, grants a special unemployment benefit scheme. In short, dancers are more protected and even socially are held in a different regard than in Italy.

About Ballet Preljocaj, when and how did you get in the company?

It was 2006. At that time I worked for two companies: Georges Momboye in Paris and Thor in Belgium. I auditioned for Preljocaj when the company was still at the Cité du Livre in Aix-en-Provence, then we moved to the new Pavillon Noir center (there is still my name – along with that of the other dancers – engraved on one of the steps of the center!). The experience with Preljocaj was very nice, I learned a lot about precision, speed and above all about how to “live” in such a big company, which was always on tour. But after two years I started feeling the need to do something different, to explore new possibilities of movement, so once again I changed, I moved to Holland.

Did you find what you were looking for in the Dansgroep Amsterdam directed by Itzik Galili & Krisztina De Chatel?

Only partially. Preljocaj is a great choreographer, but his work is mainly choral and the dancers are at acting in service to his creativity. In this sense, we had to conform to each other, to the detriment of the individual characteristics of each dancer. This is why, while realizing how important it was to learn his style and take as much of his teachings as possible, at one point I wanted to experience something different. With Galili, I certainly found more freedom. His was a more fluid movement, with a different approach and training, but it still wasn’t what I was looking for.

Is it correct to say that the turning point came with Wayne McGregor?

Absolutely! The three years I spent in London with Random Dance were among the most important, not only for my professional training, but also for my artistic and human sensitivity. What Wayne McGregor gave me was very fulfilling on both counts. His work is very interesting, it stimulates the connection between mind and body. Often, to give a theoretical foundation to his research, he collaborates with neuro-scientists who support his intuitions. With him, in fact, it is not simply a matter of learning a dance sequence and repeating it, but of facing a real challenge with oneself in order to create this connection. If on the surface his form of dance may seem cold and technical, by carefully observing his choreographies it is clear that instead it is the physicality that is able to bring you to a much more intimate level, which transcends the body. This aspect of his work is the most interesting feature, but this is not the only thing that he passed on to me.

What other teachings did he gave you?

The ability to manage and organize – with professionalism and with the necessary sensitivity for each individual – a group of people, to achieve a performance. During the time I spent in the company, I periodically had to give workshops to students, children or elderly people who had no experience in dance. Through these laboratories, so-called ‘creative learning‘, not only did I learn to manage a group and always adapt myself to different people and situations, but I also learned to use the creativity of others, to the point of succeeding with the materials of those participating in the workshops, to create real choreography.

Wayne McGregor also gave you a lot of confidence. Can you tell me how and when did you start doing your choreography for some of the major dance companies?

It was precisely through the experience acquired with creative learning and thanks to my work in the company (in particular my ability to feel the connection between mind and body that is so important for him), that in 2013 Wayne McGregor proposed me position of re-stager. I started with small jobs, first working by his side and then by myself. It is a great responsibility, but an even greater sense of satisfaction to travel the world doing this beautiful job for companies such as: Ballet de l’Opéra National de Paris, Joffrey Ballet Chicago, Hessisches Staats Ballet, Ballet Junior de Genève, TISCH School of the Arts at New York University, Milano Contemporary Ballet, Teatro alla Scala di Milano, The Royal Ballet, Polish National Ballet.

But let’s move on… How did the collaboration with Sasha Waltz come about?

After a period in Athens with Andonis Foniadakis’ Apotosoma Dance Company, I went back to Italy where I worked with Virgilio Sieni. In that same period I was invited by Sasha Waltz, who I had met years earlier at the inauguration of the Maxxi in Rome, to participate in a workshop by the Blue Company that she was hosting. It was a week of improvisation and six shows. At the end of the workshop another chapter of my professional life opened up: I started dancing for Sasha Waltz & Guests and then working as assistant choreographer and rehearsal director for the company.

There are still a couple of things I’d like to ask you …

Based on your experiences around the world, what is your relationship and what do you think about dance in Italy?

I must say that for a long time, when I went to teach in Italy, I always found very good dancers (many of them work in companies all over the world), but the level of dance was not up to that of some other European countries. Moreover, in Italy I still have the impression that dance is a closed system. Despite the experiences abroad, I have always had to fight to be paid fairly and I have always had the feeling that if you are young, despite your resumé, you will never be considered for important positions. As evidence of this, I can say that only after re-staging a piece by Wayne McGregor for Alla Scala in Milan, my name consequently started to be associated with the famous opera house and only then did my reputation grow significantly. This says a lot about how things work in our country. I must acknowledge, however, that more and more, in recent times, I find small realities that seek to promote research and a more ‘international’ form dance.

If you could make a wish for your professional future, what would you still like to achieve?

I certainly want to improve and grow as a re-stager and as a dancer, I feel I still have a lot to give and seek. These are the things I will try to do in my professional future, but if I had to hope for another goal, I think I would like to work with Pina Baush’s Tanztheater Wuppertal or with Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rosas.

Davide, thank you very much and all the best of luck.

Nicola Campanelli

iscriviti alla newsletter di Campadidanza